In previous sections, we’ve looked at each of the individual puzzle pieces that go into making a final exposure. To recap:

Shutter speed controls motion blur (or lack thereof) as well as the amount of time that light can strike the sensor (or film). The longer we keep the shutter open, the more light that will hit the sensor. At the same time, if the shutter is kept open for too long, items in the picture may look blurry from movement.

Aperture controls the depth of field (how much of the image is in focus), as well as the amount of light that can hit the sensor. Generally speaking, as we increase the size of the aperture, we decrease the amount of our image that will be in focus. Additionally, if we use a wider aperture more light will hit the camera sensor. Don’t forget: larger apertures are expressed as smaller numbers: f/2.8 lets in more light than f/22.

The ISO is the measure of how sensitive a digital sensor or film is to light. As we increase ISO, the more sensitive our sensor is. However, as we increase the ISO, the more likely we are to introduce “noise” into our exposure, degrading image quality.

So…how do we put this all together? Basically, as we change one of the above items, we need to change the other two to ensure a correct exposure. To help illustrate this, let’s do a tiny bit of algebra:

Shutter Speed + Aperture + ISO = Exposure

Forget for a second what the real values of those need to be; let’s assume that they should all be a value of 1, whatever that means. By adding them up, our correct exposure should be 3:

S + A + I = E

1 + 1 + 1 = 3

Let’s say that we want to double our shutter speed because we’re getting motion blur. If we still want an exposure value of 3, we will need to adjust either our aperture or our ISO, like so:

S + A + I = E

2 + 0 + 1 = 3 or

2 + 1 + 0 =3

If we double our shutter speed but don’t compensate by changing one of the other items (aperture or ISO), our exposure will be too dark. In this case, we get a value of 4, which is wrong:

S + A + I = E

2 + 1 + 1 = 4

In the real world, which of the three exposure pieces you change will depend on a number of factors, but most often it will be for creative control. For example, let’s say that you want a very shallow depth of field, so you open the aperture as wide as you can. In doing so, you may let in too much light, so you can make the shutter speed faster (e.g. go from 1/125s to 1/250s), or can decrease the ISO (e.g. 400 to 200).

Suppose your camera is set to the following: 1/125s, f/4, and ISO 1600. You look at the picture and are unhappy with the graininess resulting from the high ISO. To compensate, you step the ISO down to 400. If you don’t change the aperture or shutter speed, your image will be too dark. So which do we change?

If we slow down the shutter speed to 1/30s, we’ll let in enough light, but our subject might get blurry. And unless you have a really expensive lens (or something called a “prime” lens), there’s a good chance you won’t be able to open your aperture past f/2.8, which you would need.

The answer then is probably to change both. If we change the ISO from 1600 to 400, we’re adjusting the exposure 2 stops. We can recover those stops by changing the shutter speed and aperture 1 stop each. In this case, that would mean changing the shutter to 1/60s and the aperture to f/2.8. At 1/60s, it’s possible you may be able to avoid a blurry subject, in which case your exposure will have worked.

The easiest way to begin expirmenting with these relationships is to try out your camera in either aperture or shutter priority modes. In these modes, you pick either the aperture or shutter speed, and the camera automatically sets the other one for you. Try using the camera in one of these modes and then changing the aperture/shutter speed. See what the camera does to the other when you make the change.

I still had difficulty getting a fast enough shutter speed to freeze him. Next time we meet for a shoot I’ll explain the finer points of shutter speed and aperture. Maybe then he’ll sit still for a bit. ;)

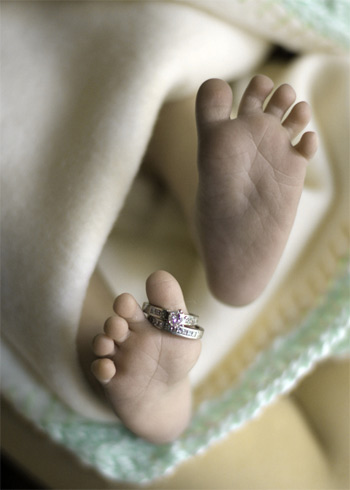

with 50mm f/1.4 lens

, Expodisc warm balance filter

, Smith Victor basic light kit

and Port-a-Stand background stand

.